Saturday, October 29, 2011

Thinking out loud

We humans are a varied lot. We perceive matters differently. Ask any 10 witnesses to an incident what they saw and you will receive 10 different accounts. We also react differently to stimulus. This is not a bad thing. All of us are unique and wired differently. We are the sum of our experiences from birth to the present. No two human experiences are exactly the same, therefore we can only perceive certain similarities in others and ourselves.

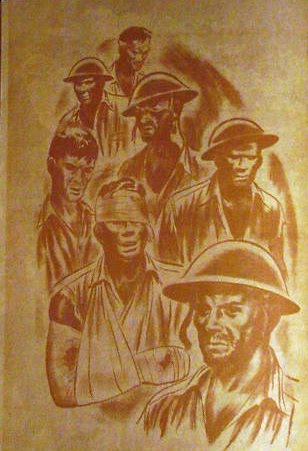

When I give thought to military prisoners of the Japanese after the collapse of the Philippines whom I have met, including my father, I find they neatly fit into three categories. First are the the men who do not talk at all, do not attend conventions, nor want anything to do with those that do.They go to the grave taking their demons with them.

The second group are those who reluctantly speak about the horrors they witnessed. Alcohol tends to lubricate their hesitancy and they'll recount some stories which often end in an emotional shutdown. They tend to tell what they consider funny stories which occurred during their saga and relieves their tension somewhat.

The third group are those that have managed in some way to isolate their emotions from their experiences and are the ones who have written books, magazine articles and are willing to share of themselves during panel discussions and question and answer periods afterward. They have educated us about the battle and imprisonment with first hand accounts. This does not mean that these men do not have emotional periods but they are better suited to contain their memories and keep them leashed.

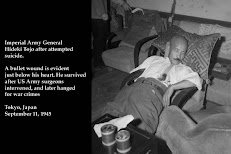

There is a forth group but their numbers are so small that in my opinion, they do not constitute a group. These men vanished early after repatriation for the most part. They could not take flight from their memories. They were engulfed and drowning in the misery of their past. The human ugliness of the enemy and even among their own ranks was too much to bear. Death for them had become so commonplace that life had little meaning other than a prolongation of suffering. These men in various ways ended their existence.

Personally, my father fit into group two. I could not question him about the war unless he was somewhat intoxicated. This was the only time he could speak of the human drama in war. Seeing his comrades explode into pieces of bloody composition, holding a young soldier in his arms and comforting him as he died, watching his friends and buddies slowly die of starvation and disease and to be absolutely helpless to do anything about it. This was his hell and he could tolerate his thoughts for so long even with the alcohol.

When sober and questioned, his only stories were those funny episodes, for example, how he caught the camp commandants dog and he and his buddies killed. cooked and ate it. All the time telling the story with a short stuttering laugh as though trying to choke back sobs.

At the 2010 convention of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor held by the Descendants Group in Reno, Nevada, I asked Ben Steele, a well known pow, to tell me about a funny experience he had as a prisoner. His answer gave me some insight into how bad his experience must have been to consider what he told me was "funny".

He began his funny story as he was descending a ladder in to the Hellship, Canadian Inventor, on Pier 7 in Manila. As he was descending slowly, the pow above him coming down the ladder must have had dysentery and couldn't hold his bowels and let go all over Ben's head and shoulders. Ben said, "you know Bob, I had no cloth or towel or water to wipe the excrement off my head and shoulders. I had to sit in the hold of that ship for hours and wait until it dried and then peeled it off myself". He then chuckled. I found myself crying, knowing that I would never understand the humor in his experience. I would never understand how bad the situation was that he considered this humorous.

I cannot conceive of surviving such a circumstance. These men, no matter what group they fit into, survived an indescribable experience. All the books by and about pow's can never more circle the rim of their experiences. Even these men who sit in small rooms and speak of their ordeals, struggle to find the adjectives, as they have those thousand yard stares on their faces and search the past in their minds eye.

Who are we to kid ourselves that we will ever understand the totality of their encounter with the mindlessness and ugliness of mans destructive nature. We worry too much about an asteroid striking and destroying the Earth and not enough about our nature striking and destroying the Earth. This will be our undoing. We need to keep this in mind and teach our children its lessons.

Robert Hudson 10/29/2011

When I give thought to military prisoners of the Japanese after the collapse of the Philippines whom I have met, including my father, I find they neatly fit into three categories. First are the the men who do not talk at all, do not attend conventions, nor want anything to do with those that do.They go to the grave taking their demons with them.

The second group are those who reluctantly speak about the horrors they witnessed. Alcohol tends to lubricate their hesitancy and they'll recount some stories which often end in an emotional shutdown. They tend to tell what they consider funny stories which occurred during their saga and relieves their tension somewhat.

The third group are those that have managed in some way to isolate their emotions from their experiences and are the ones who have written books, magazine articles and are willing to share of themselves during panel discussions and question and answer periods afterward. They have educated us about the battle and imprisonment with first hand accounts. This does not mean that these men do not have emotional periods but they are better suited to contain their memories and keep them leashed.

There is a forth group but their numbers are so small that in my opinion, they do not constitute a group. These men vanished early after repatriation for the most part. They could not take flight from their memories. They were engulfed and drowning in the misery of their past. The human ugliness of the enemy and even among their own ranks was too much to bear. Death for them had become so commonplace that life had little meaning other than a prolongation of suffering. These men in various ways ended their existence.

Personally, my father fit into group two. I could not question him about the war unless he was somewhat intoxicated. This was the only time he could speak of the human drama in war. Seeing his comrades explode into pieces of bloody composition, holding a young soldier in his arms and comforting him as he died, watching his friends and buddies slowly die of starvation and disease and to be absolutely helpless to do anything about it. This was his hell and he could tolerate his thoughts for so long even with the alcohol.

When sober and questioned, his only stories were those funny episodes, for example, how he caught the camp commandants dog and he and his buddies killed. cooked and ate it. All the time telling the story with a short stuttering laugh as though trying to choke back sobs.

At the 2010 convention of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor held by the Descendants Group in Reno, Nevada, I asked Ben Steele, a well known pow, to tell me about a funny experience he had as a prisoner. His answer gave me some insight into how bad his experience must have been to consider what he told me was "funny".

He began his funny story as he was descending a ladder in to the Hellship, Canadian Inventor, on Pier 7 in Manila. As he was descending slowly, the pow above him coming down the ladder must have had dysentery and couldn't hold his bowels and let go all over Ben's head and shoulders. Ben said, "you know Bob, I had no cloth or towel or water to wipe the excrement off my head and shoulders. I had to sit in the hold of that ship for hours and wait until it dried and then peeled it off myself". He then chuckled. I found myself crying, knowing that I would never understand the humor in his experience. I would never understand how bad the situation was that he considered this humorous.

I cannot conceive of surviving such a circumstance. These men, no matter what group they fit into, survived an indescribable experience. All the books by and about pow's can never more circle the rim of their experiences. Even these men who sit in small rooms and speak of their ordeals, struggle to find the adjectives, as they have those thousand yard stares on their faces and search the past in their minds eye.

Who are we to kid ourselves that we will ever understand the totality of their encounter with the mindlessness and ugliness of mans destructive nature. We worry too much about an asteroid striking and destroying the Earth and not enough about our nature striking and destroying the Earth. This will be our undoing. We need to keep this in mind and teach our children its lessons.

Robert Hudson 10/29/2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

1 comment:

Thank you for sharing this very personal recollection about your father. I've been wanting to start a blog about WWII books and films, but I'm afraid to dishonor what your father's generation went through by being too flippant. I'm still trying to decide if/how I should do it.

Post a Comment